by Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Hotel History: The Greenbrier (682 rooms)

The original hotel, the Grand Central Hotel, was built on this site in 1858. It was known as “The White” and later “The Old White”. Beginning in 1778, people came to follow the local Native American tradition to “take the waters” to restore their health. In the 19th century, visitors drank and bathed in the sulphur water to cure everything from rheumatism to an upset stomach

In 1910, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway purchased the historic resort property and embarked upon a major expansion. By 1913, the railroad had added The Greenbrier Hotel (the central section of today’s hotel), a new mineral bath department ( the building that includes the grand indoor pool) and an 18-hole golf course (now called The Old White Course) designed by the most prominent contemporary golf architect, Charles Blair Macdonald. In 1914, for the first time, the resort, now renamed The Greenbrier, was open year-round. That year, President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson spent their Easter holiday at The Greenbrier.

Business boomed in the 1920s and The Greenbrier took its place within high society’s traveling network that stretched from Palm Beach, Florida to Newport, Rhode Island. The obsolete Old White Hotel was demolished in 1922, which led to a substantial rebuilding of The Greenbrier Hotel in 1930. This refurbishment doubled the number of guestrooms to five hundred. Cleveland architect Philip Small redesigned the hotel’s main entrance and added both the Mount Vernon-inspired Virginia Wing to the south and the signature North Entrance facade. Mr. Small’s design mixed elements from the resort’s Southern historical roots with motifs from the Old White Hotel.

During the Second World War, the United States government appropriated The Greenbrier for two very different uses. First, the State Department leased the hotel for seven months immediately after the U.S. entry into the war. It was used to relocate hundreds of German, Japanese, and Italian diplomats and their families from Washington, D.C. until their exchange for American diplomats, similarly stranded overseas, was completed. In September 1942, the U.S. Army purchased The Greenbrier and converted it into a two thousand-bed hospital named Ashford General Hospital. In four years, 24,148 soldiers were admitted and treated, while the resort served the war effort as a surgical and rehabilitation center. Soldiers were encouraged to use the resort’s range of sports and recreation facilities as part of their recuperation process. At the war’s conclusion, the Army closed the hospital.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway reacquired the property from the government in 1946. The company immediately commissioned a comprehensive interior renovation by the noted designer Dorothy Draper. As Architectural Digest described her, Draper was “a true artiest of the design world [who] became a celebrity in the modern sense of the word, virtually creating the image of the decorator in the popular mind.” She remained the resort’s decorator into the 1960s. Upon her retirement, her protégé Carleton Varney purchased the firm and became The Greenbrier’s decorating consultant.

When The Greenbrier reopened in 1948, Sam Snead returned as golf pro to the resort where his career had begun in the late 1930s. For two decades in the post war years, he traveled the globe at the pinnacle of his lengthy career. More than any other individual, Sam Snead established The Greenbrier’s reputation as one of the world’s foremost golf destinations. In later years, he was named Golf Pro Emeritus, a position he held until his death on May 23, 2002.

In the late 1950s, the U.S. government once again approached The Greenbrier for assistance, this time in the construction of an Emergency Relocation Center ̶ a bunker or bomb shelter ̶ to be occupied by the U.S. Congress in case of war. Built during the cold war and operated in secrecy for 30 years, it is a huge 112,000 square foot underground fallout shelter, intended for use by the entire United States Congress in the event of nuclear war.

Excavations began in 1958 and construction was completed in 1962. By top-secret agreement, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway built a new addition to the resort, the West Virginia Wing and the bunker was surreptitiously constructed under it. With concrete walls up to five feet thick, it is the size of two football fields stacked underground. It was built to shelter 1100 people: 535 senators and representatives and their aides. For the next 30 years, government technicians, posing as employees of a dummy company, Forsythe Associates, maintained the place regularly checking its communications and scientific equipment as well as updating the magazines and paperbacks in the lounge areas. At any point during those years, one telephone call from officials in Washington, D.C., fearing an imminent attack on the capital, would have turned the lavish resort into an active participant in the national defense system. At the end of the Cold War and prompted by exposure in the press in 1992, the project was terminated and the bunker decommissioned. According to a May 6, 2013 article in the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. Supreme Court planned to relocate to the Grove Park Inn, Asheville, N.C. in the event of a nuclear attack.

In the overt world above the bunker, resort life proceeded normally as Jack Nicklaus arrived to redesign the fifty-year old Greenbrier Course, bringing it up to championship standards for the 1979 Ryder Cup Matches. That course was also the site of three PGA Seniors tournaments in the 1980s and the 1994 Solheim Cup competition. In 1999, the Meadows Course evolved when Bob Cupp redesigned, rerouted and upgraded the older Lakeside Course, a project that included the creation of new Golf Academy. Sam Snead’s career was enshrined when the Golf Club was virtually rebuilt featuring the restaurant bearing his name with museum quality displays of memorabilia from his personal collection.

In a surprise announcement on May 7, 2009, Jim Justice, a West Virginia entrepreneur with a long-standing appreciation for The Greenbrier, became the owner of America’s most fabled resort. He purchased it from the CSX Corporation which, through its predecessor companies the Chessie System and the C&O Railway, had owned the resort for ninety-nine years. Mr. Justice turned his considerable energies into plans to revitalize America’s Resort. He immediately presented his vision of a casino designed by Carleton Varney that included shops, restaurants and entertainment in a smoke-free environment. The Casino Club at The Greenbrier opened in grand fashion on July 2, 2010. Simultaneously, Mr. Justice arranged to relocate a PGA Tour event named The Greenbrier Classic under the direction of The Greenbrier’s new Golf Pro Emeritus, Tom Watson. The first tournament was held July 26 through August 1, 2010.

Twenty-six presidents have stayed at The Greenbrier. The President’s Cottage Museum is a two-story building with exhibits about these visits and the history of The Greenbrier. The Greenbrier is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a member of Historic Hotels of America. It is a Forbes Four-Star and AAA Five-Diamond Award winner.

The Greenbrier’s complete history is chronicled in great detail supplemented by photographs from the resort’s archives in The History of The Greenbrier: America’s Resort by Dr. Robert S. Conte, the resort’s Resident Historian since 1978.

My Latest Book “Great American Hotel Architects Volume 2” was published in 2020.

All of my following books can be ordered from AuthorHouse by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com and clicking on the book’s title:

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

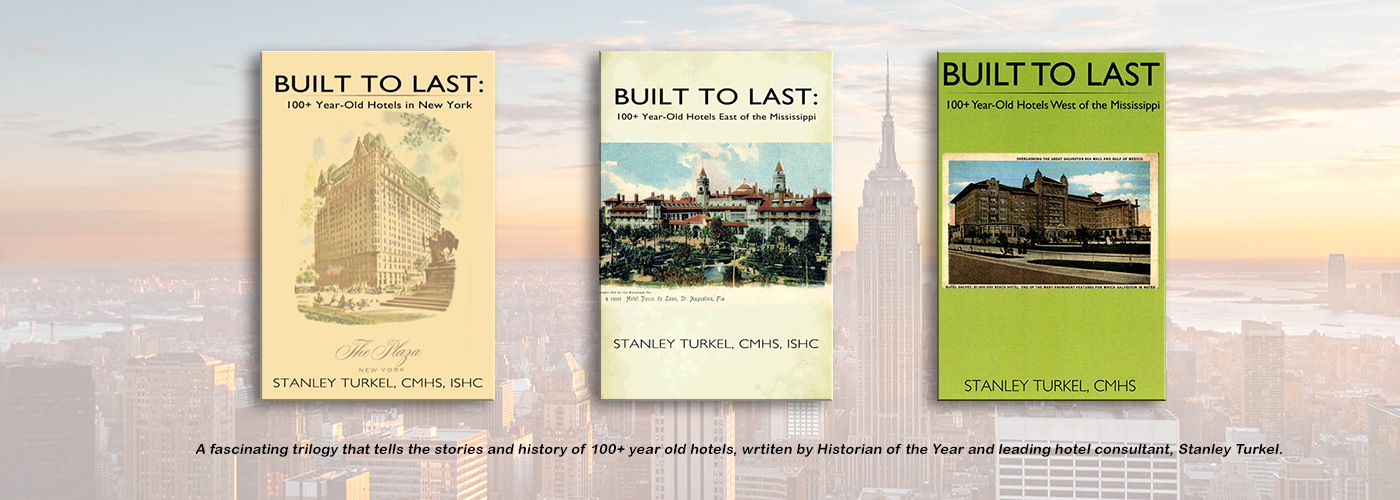

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt, Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume I (2019)

- Hotel Mavens: Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

If You Need an Expert Witness:

Stanley Turkel has served as an expert witness in more than 42 hotel-related cases. His extensive hotel operating experience is beneficial in cases involving:

- slip and fall accidents

- wrongful deaths

- fire and carbon monoxide injuries

- hotel security issues

- dram shop requirements

- hurricane damage and/or business interruption cases

Feel free to call him at no charge on 917-628-8549 to discuss any hotel-related expert witness assignment.![]() 269

269

ABOUT STANLEY TURKEL

Stanley Turkel was designated as the 2020 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He had previously been so designated in 2015 and 2014.

This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of historic hotels and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion of greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Turkel is the most widely-published hotel consultant in the United States. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases, provides asset management and hotel franchising consultation. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

Categories

- Industry Happenings (25,931)

- Latest news (8,806)

- Technology (5,253)

- Operations (3,904)

- All Things Independent (3,727)

- Market Reports (1,954)

- Development (1,792)

- Appointments/People on the Move (1,467)

- Finance (1,250)

- Smart Strategies (1,232)

hotelonlinenewsInstagram post 18072439732009889Instagram post 18037678936156831Instagram post 17870090452391124Instagram post 17976176743256949Instagram post 17993811919233333Follow on Instagram

Tags

historic hotelhotel historynobody asked mestanley turkelthe greenbrier

RELATED NEWS:

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 258: Hotel History: The Willard Hotel, Washington, D.C.Nobody Asked Me, But…. No. 257: Hotel History: El Tovar & Hopi Gift ShopNobody Asked Me, But… No. 256: Hotel History: Severin Hotel Indianapolis, IndianaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 255: Hotel History: Shelton Hotel, New YorkNobody Asked Me, But… No. 254: Hotel History: St. Regis HotelNobody Asked Me, But… No. 253; Hotel History: Hotel PennsylvaniaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 252: Hotel History: Libby’s Hotel and BathsNobody Asked Me, But… No. 251: Wish You Were Here: A Tour of America’s Great Hotels During the Golden Age of the Picture Post CardNobody Asked Me, But… No. 250: Hotel History: Mohonk Mountain House, New Paltz, New YorkNobody Asked Me, But… No. 249: Hotel History: Ocean House at Watch HillNobody Asked Me, But… No. 248: Hotel Theresa, New York, N.Y. (1913)Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 247: Hotel History: Driskill Hotel, Austin, TexasNobody Asked Me, But… No. 246: Hotel History: Hotel McAlpin, New York, N.Y. (1912)Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 245: Boone Tavern Hotel, Berea, Kentucky (1855)Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 244: Hotel History: Wormley HotelNobody Asked Me, But… No. 243: Hotel History: Hotel Roanoke, VirginiaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 242: Hotel History: Fisher Island, Miami, FloridaStanley Turkel Named the Recipient of the 2020 Historic Hotels of America Historian of the Year AwardNobody Asked Me, But… No. 241: Hotel History: Menger HotelNobody Asked Me, But… No. 240 Fairmont Le Chateau Frontenac, Quebec City, Canada (1893)