Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 260: Hotel History: Terminal City, The Roosevelt Hotel and The Postum Building, New York

Stanley Turkel | January 25, 2022

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Hotel History: Terminal City (1911)

Terminal City originated as an idea during the reconstruction of Grand Central Terminal from the old Grand Central Station from 1903 to 1913. The railroad owner, the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, wished to increase capacity of the station’s train shed and rail yards, and so it devised a plan to bury the tracks and platforms and create two levels to its new train shed, more than doubling the station’s capacity. At the same time, chief engineer William J. Wilgus was the first to realize the potential of selling air rights, the right to build atop the now-underground train shed, for real-estate development. Grand Central’s construction thus produced several blocks of prime real estate in Manhattan, stretching from 42nd to 51st Streets between Madison and Lexington Avenues. The Realty and Terminal Company typically profited from the air rights in one of two ways: constructing the structures and renting them out, or selling the air rights to private developers who would construct their own buildings.

William Wilgus saw these air rights as a means of funding the terminal’s construction. Architects Reed & Stem originally proposed a new Metropolitan Opera House, a Madison Square Garden, and a National Academy of Design building. Ultimately, the railroad decided to develop the area into a commercial office district.

Planning for the development began long before the terminal was completed. In 1903, the New York Central Railroad created a derivative, the New York State Realty and Terminal Company, to oversee construction above Grand Central’s rail yards. The New Haven Railroad joined the venture later on. The blocks on the north side of the terminal were later dubbed “Terminal City” or the “Grand Central Zone”.

By 1906, news of the plans for Grand Central was already boosting the values of nearby properties. In conjunction with this project, the segment of Park Avenue above Grand Central’s rail yards received a landscaped median and attracted some of the most expensive apartment hotels. By the time the terminal opened in 1913, the blocks surrounding it were each valued at $2 million to $3 million. Terminal City soon became Manhattan’s most desirable commercial and office district. From 1904 to 1926, land values along Park Avenue doubled, and in the Terminal City area increased 244%. A 1920 New York Times article said that the “development of the Grand Central property has in many respects surpassed original expectations. With its hotels, office buildings, apartments and underground streets it not only is a wonderful railroad terminal, but also a great civic centre.”

The district came to include office buildings such as the Grand Central Palace, Chrysler Building, Chanin Building, Bowery Savings Bank Building, and Pershing Square Building; luxury apartment houses along Park Avenue; an array of high-end hotels that included the Commodore, Biltmore, Roosevelt, Marguery, Chatham, Barclay, Park Lane, Waldorf Astoria and the Yale Club of New York.

These structures were designed in the neoclassical style, complementing the terminal’s architecture. Although Architects Warren and Wetmore designed most of these buildings, it also monitored other architects’ plans (such as those of James Gamble Rogers, who designed the Yale Club) to ensure that the style of the new buildings was compatible with that of Terminal City. In general, the site plan of Terminal City was derived from the City Beautiful movement, which encouraged aesthetic harmony between adjacent buildings. The consistency of the architectural styles, as well as the vast funding provided by investment bankers, contributed to Terminal City’s success.

The Graybar Building, completed in 1927, was one of the last projects of Terminal City. The building incorporates many of Grand Central’s train platforms, as well as the Graybar Passage, a hallway with vendors and train gates stretching from the terminal to Lexington Avenue. In 1929, New York Central built its headquarters in a 34-story building, later renamed the Helmsley Building, which straddled Park Avenue north of the terminal. Development slowed drastically during the Great Depression, and part of Terminal City was gradually demolished or reconstructed with steel-and-glass designs after World War II.

The City Club of New York, (where I served as Chairman of the Board from 1979 to 1990) recently sent a letter to the N.Y. Landmarks Preservation Commission urging Landmarks protection for the Hotel Roosevelt (George B. Post and Son 1924) and the Postum Building (Cross & Cross 1923).

The Roosevelt Hotel is a historic hotel located at 45 East 45th Street (between Madison Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue) in Midtown Manhattan. Named in honor of President Theodore Roosevelt, the Roosevelt opened on September 22, 1924. It closed permanently on December 18, 2020.

There are a total of 1,025 rooms in the hotel, including 52 suites. The 3,900-square-foot Presidential Suite has four bedrooms, a kitchen, formal living and dining areas, and a wrap-around terrace. The rooms are traditionally decorated, with mahogany wood furniture and light-colored bed coverings.

There were several restaurants within the hotel, including:

- “The Roosevelt Grill”, serving American food and regional specialties for breakfast.

- The “Madison Club Lounge”, a bar and lounge with a 30-foot mahogany bar, stained glass windows, and a pair of fireplaces.

- The “Vander Bar”, a bistro with modern décor, serving craft beers

The Roosevelt has 30,000 square feet of meeting and exhibit space, including two ballrooms and 17 additional meeting rooms ranging in size from 300 to 1,100 square feet.

The Roosevelt Hotel was built by Niagara Falls businessman Frank A. Dudley and operated by the United Hotels Company. The hotel was designed by the firm of George B. Post & Son, and leased from The New York State Realty and Terminal Company, a division of the New York Central Railroad. The hotel, built at a cost of $12,000,000 (equivalent to $181,212,000 in 2020), was the first to incorporate store fronts instead of bars in its sidewalk facades, as the latter had been prohibited due to Prohibition. The Roosevelt Hotel was at one time linked with Grand Central Terminal via an underground passage that connected the hotel to the train terminal. The passageway now terminates just across the street from the hotel’s East 45th Street entrance. The Roosevelt housed the first guest pet facility and child care service in The Teddy Bear Room and had the first in-house doctor.

Hilton

Conrad Hilton purchased the Roosevelt in 1943, calling it “a fine hotel with grand spaces” and making the Roosevelt’s Presidential Suite his home. In 1947, the Roosevelt became the first hotel to have a television set in every room.

Hilton Hotels purchased the Statler Hotels chain in 1954. As a result, they owned multiple large hotels in many major cities, as in New York, where they owned the Roosevelt, The Plaza, The Waldorf-Astoria, the New Yorker Hotel and the Hotel Statler. Soon after, the federal government filed an antitrust action against Hilton. To resolve the suit, Hilton agreed to sell a number of their hotels, including the Roosevelt Hotel, which was sold to the Hotel Corporation of America on February 29, 1956 for $2,130,000.

Pakistan International Airlines

By 1978, the hotel was owned by the struggling Penn Central, which put it up for sale, along with two other nearby hotels, The Biltmore and The Barclay. The three hotels were sold to the Loews Corporation for $55 million. Loews immediately resold the Roosevelt to developer Paul Milstein for $30 million.

In 1979, Milstein leased the hotel to the Pakistan International Airlines with an option to purchase the building after 20 years at a set price of $36.5 million. Prince Faisal bin Khalid Abdulaziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia was one of the investors in the 1979 deal. The hotel lost its operators $70 million over the following years, due to its outdated facilities.

In 2005, PIA bought out its Saudi partner in a deal that included the prince’s share in the Hôtel Scribe in Paris, in exchange for $40 million and PIA’s share of the Riyadh Minhal Hotel (a Holiday Inn located on property owned by the prince). In July 2007, PIA announced that it was putting the hotel up for sale. The increasing profitability of the hotel, at the same time as the airline itself started to incur massive losses, resulted in the sale being abandoned. In 2011, The Roosevelt once again underwent extensive renovations, but remained open during the process.

In October 2020, it was announced the hotel would permanently close due to continued financial losses associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The final day of operation was December 18, 2020.

Guy Lombardo began leading the house band of the Roosevelt Grill in 1929; it was here that Lombardo also began holding an annual New Year’s Eve radio broadcast with his band, The Royal Canadians.

Lawrence Welk began his career at the Roosevelt Hotel in the summers when Lombardo took his music to Long Island. Music was piped live into each room via radio. Hugo Gernsback (of Hugo Award fame) started WRNY from a room on the 18th floor of the Roosevelt Hotel broadcasting live via a 125-foot tower on the roof.

From 1943 to 1955 the Roosevelt Hotel served as the New York City office and residence of Governor Thomas E. Dewey. Dewey’s primary residence was his farm in Pawling, in upstate New York, but he used Suite 1527 in the Roosevelt to conduct most of his official business in the city. In the 1948 presidential election, which Dewey lost to incumbent President Harry S. Truman in a major upset, Dewey, his family, and staff listened to the election returns in Suite 1527 of the Roosevelt.

Terminal City, the Roosevelt Hotel and the Postum Building are the heart of New York. They should be given Landmarks designation and protection as soon as possible since the Roosevelt Hotel is closed and the owners of the Postum building have hired an architect to “explore options”.

My Latest Book “Great American Hotel Architects Volume 2” was published in 2020.

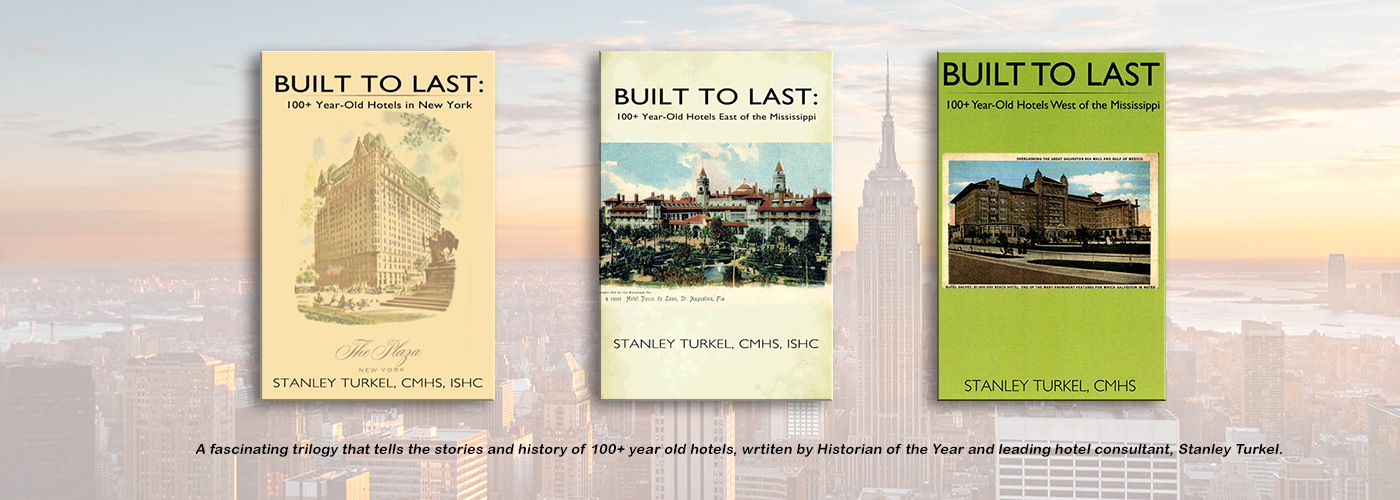

All of my following books can be ordered from AuthorHouse by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com and clicking on the book’s title:

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt, Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume I (2019)

- Hotel Mavens: Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

If You Need an Expert Witness:

Stanley Turkel has served as an expert witness in more than 42 hotel-related cases. His extensive hotel operating experience is beneficial in cases involving:

- slip and fall accidents

- wrongful deaths

- fire and carbon monoxide injuries

- hotel security issues

- dram shop requirements

- hurricane damage and/or business interruption cases

Feel free to call him at no charge on 917-628-8549 to discuss any hotel-related expert witness assignment.![]() 147

147

ABOUT STANLEY TURKEL

Stanley Turkel was designated as the 2020 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He had previously been so designated in 2015 and 2014.

This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of historic hotels and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion of greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Turkel is the most widely-published hotel consultant in the United States. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases, provides asset management and hotel franchising consultation. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

Categories

- Industry Happenings (25,956)

- Latest news (9,066)

- Technology (5,278)

- Operations (3,909)

- All Things Independent (3,727)

- Market Reports (1,967)

- Development (1,817)

- Appointments/People on the Move (1,521)

- Finance (1,252)

- Smart Strategies (1,235)

hotelonlinenewsInstagram post 18072439732009889Instagram post 18037678936156831Instagram post 17870090452391124Instagram post 17976176743256949Instagram post 17993811919233333Follow on Instagram

Tags

hotel historynobody asked mestan turkelstanley turkelthe roosevelt hotel

RELATED NEWS:

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 259: Hotel History: The Greenbrier, White Sulphur Springs, West VirginiaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 258: Hotel History: The Willard Hotel, Washington, D.C.Nobody Asked Me, But…. No. 257: Hotel History: El Tovar & Hopi Gift ShopNobody Asked Me, But… No. 256: Hotel History: Severin Hotel Indianapolis, IndianaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 255: Hotel History: Shelton Hotel, New YorkNobody Asked Me, But… No. 254: Hotel History: St. Regis HotelNobody Asked Me, But… No. 253; Hotel History: Hotel PennsylvaniaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 252: Hotel History: Libby’s Hotel and BathsNobody Asked Me, But… No. 251: Wish You Were Here: A Tour of America’s Great Hotels During the Golden Age of the Picture Post CardNobody Asked Me, But… No. 250: Hotel History: Mohonk Mountain House, New Paltz, New YorkNobody Asked Me, But… No. 249: Hotel History: Ocean House at Watch HillNobody Asked Me, But… No. 248: Hotel Theresa, New York, N.Y. (1913)Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 247: Hotel History: Driskill Hotel, Austin, TexasNobody Asked Me, But… No. 246: Hotel History: Hotel McAlpin, New York, N.Y. (1912)Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 245: Boone Tavern Hotel, Berea, Kentucky (1855)Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 244: Hotel History: Wormley HotelNobody Asked Me, But… No. 243: Hotel History: Hotel Roanoke, VirginiaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 242: Hotel History: Fisher Island, Miami, FloridaStanley Turkel Named the Recipient of the 2020 Historic Hotels of America Historian of the Year AwardNobody Asked Me, But… No. 241: Hotel History: Menger Hotel