Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 266: Hotel History: The Palace Hotel, San Francisco, California

Stanley Turkel | June 01, 2022

by Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Hotel History: The Palace Hotel (1909), San Francisco, Ca (556 rooms)

San Francisco and the Palace Hotel have shared a common heritage for more than 140 years. Inspired by a visionary developer, William Chapman Ralston, the Palace Hotel was known as the “Grande Dame of the West”, a hotel of timeless elegance and unprecedented opulence. It was designed by architect John P. Gaynor as the largest, costliest and most luxurious hotel in the world. To finance its $5 million cost, Ralston exhausted his Bank of California which collapsed in late August 1875. Soon thereafter, Ralston’s body was found floating in San Francisco Bay. Nevertheless, the Palace Hotel opened two months later on October, 1875. Nevada’s U.S. Senator William Sharon, one of Ralston’s partners, who was known as the “King of the Comstocks” ended up in control of the hotel when he paid off the Bank and Ralston’s debts with pennies on the dollar.

San Francisco and the Palace were both destroyed in the earthquake and fire of 1906. Before that tragedy, the original hotel featured the Grand Court, the carriage entrance which was surrounded by seven floors of balconies bedecked in tropical plants and lighted by hundreds of gas jets and was paved in marble and roofed in opaque glass. The guests were distinguished: Don Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil; King David Kalakaua, the last King of Hawaii (who died at the Palace Hotel); Rudyard Kipling, Henry Irving, Ellen Terry and Enrico Caruso. Guests were awed by the hotel’s four hydraulic elevators known as “rising rooms”. Each room was equipped with an electric call button so that every guest request could be met quickly and completely.

The following Proclamation was circulated by Mayor E.E. Schmitz:

Proclamation By The Mayor

The Federal Troops, the members of the Regular Police Force and all Special Police Officers have been authorized by me to KILL any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime.

I have directed all the Gas and Electric Lighting Co.’s not to turn on Gas or Electricity until I order them to do so. You may therefore expect the city to remain in darkness for an indefinite time.

I request all citizens to remain at home from darkness until daylight every night until order is restored.

I WARN all Citizens of the danger of fire from Damaged or Destroyed Chimneys, Broken or Leaking Gas Pipes or Fixtures, or any like cause.

E. Schmitz, Mayor

April 18, 1906.

After the earthquake and fire, it took three years of rebuilding under the supervision of the architectural firm Trowbridge & Livingston (who were renowned for the St. Regis Hotel, the Knickerbocker Hotel, and the B. Altman & Company department store in New York). To keep the tradition of the Palace alive, a small wooden “Baby Palace” hotel was quickly constructed a few blocks from the ruined hotel. It had twenty-three rooms and was managed by Ernest Arbogast, the renowned chef of the original Palace Hotel. When the Palace Hotel reopened in 1909, it featured the Maxfield Parrish 16-foot mural “The Pied Piper of Hamlin” which is displayed to this day in the Pied Piper Bar. The carriage entrance was transformed into the Garden Court, one of the world’s most beautiful public places and prestigious dining room.

The following summary describes some of the unusual events and famous people who stayed at the Palace Hotel:

- 1915: Thomas Alva Edison, the wizard of electricity, was honored by Northern California Telegraph Operators. Menus were prepared in Morse Code and orders were placed with telegraph keys along wires strung from table on miniature telegraph poles.

- 1919: President Woodrow Wilson hosted two luncheons in support of the Versailles Treaty which ended World War I.

- 1923: Warren G. Harding’s term as President ended suddenly when he died at the Palace Hotel after suffering from food poisoning while cruising the Alaska Coast aboard the presidential yacht.

- 1927: Colonel Charles Lindbergh, acclaimed as a hero because of his solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, flew to San Francisco to encourage the development of commercial aviation and construction of airports. He was honored with a major banquet at the Garden Court of the Palace Hotel.

- 1934: “The Pied Piper of Hamlin”, a famous painting by Maxfield Parrish was returned to the Palace Hotel bar after fourteen years of storage at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum during Prohibition.

- 1935-1943: Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt were guests at the Palace as well as Don Ameche, Cesar Romero, Douglas Fairbanks, Loretta Young, Tyrone Power, Daryl Zanuck and Bob Hope.

- 1943: San Francisco honored Madame Chiang Kai-shek at a magnificent banquet at the Palace Garden Court.

- 1954: Ernest Henderson, president of the Sheraton Corporation purchased the Palace Hotel and renamed it the Sheraton-Palace. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev spoke at a banquet at the Sheraton-Palace during his American tour in 1959.

- 1973: Sheraton sold the Palace to the Japanese Kyo-Ya group along with all their hotels in the Hawaiian Islands but continued to manage them.

- 1989: The Sheraton-Palace Hotel closed for extensive renovation and reopened as the Sheraton Palace (no hyphen) following a $150 million restoration.

- 1990: The hotel dropped the Sheraton name by its new owner Starwood Hotels and became part of the Luxury Collection as the Palace Hotel.

- 1991: Visitors were delighted with the results of the restoration by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, chief architects for the project and Page & Turnbull, specialists in historic restoration. The restored Garden Court, according to architectural critic Allan Temko “is not only the most resplendent room in San Francisco, but one of the largest… There are some 25,000 individual panes in the immense translucent skylight, arranged in 692 geometric panels, and every one of them has been taken down, cleaned, mended where necessary, and replaced in a rebuilt armature under a handsome new outer skylight.” Another writer placed the number of pieces of stained glass in the four-story dining room’s ornamental dome at 70,000. The restored room was highlighted by ten 700-pound crystal chandeliers. On the fourth floor was a glass-domed swimming pool and health spa.

- 1997: The David Fincher film The Game, starring Michael Douglas, was shot in the Garden Court.

- 2015: The hotel received an extensive renovation to its guest rooms, indoor pool, fitness center, lobby, promenade and the one and only Garden Court.

A review of the Palace grillroom in the late 1890s that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle was true then and, even more so, in 2016:

“Comparison? Well, there is none, for the reason that the grill room has no competitors; it has only imitators. The Palace grill room came first… then the globe trotters discovered it, and they carried its fame to the four corners of the earth… and the imitators fell into line.

The Palace grill is the fin de siècle in café, restaurant cuisine in America. It has no peer, and the zest of the Grill Room steak would bring Chateaubriand from his grave… Over its silver-framed tables and beneath its white ceiling and glittering chandeliers the great world meets to eat, to drink and talk. It has brought famine to half the club dining rooms…”

The Palace Hotel is a member of the Historic Hotels of America and the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

All of my following books can be ordered from AuthorHouse by visiting stanleyturkel.com and clicking on the book’s title:

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt, Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume I (2019)

- Hotel Mavens: Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 2 (2020)

If You Need an Expert Witness:

Stanley Turkel has served as an expert witness in more than 42 hotel-related cases. His extensive hotel operating experience is beneficial in cases involving:

- slip and fall accidents

- wrongful deaths

- fire and carbon monoxide injuries

- hotel security issues

- dram shop requirements

- hurricane damage and/or business interruption cases

Feel free to call him at no charge on 917-628-8549 to discuss any hotel-related expert witness assignment.

ABOUT STANLEY TURKEL

Stanley Turkel was designated as the 2020 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He had previously been so designated in 2015 and 2014.

This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of historic hotels and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion of greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Turkel is the most widely-published hotel consultant in the United States. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

Categories

- Industry Happenings (26,083)

- Latest news (10,617)

- Technology (5,406)

- Operations (3,971)

- All Things Independent (3,738)

- Market Reports (2,073)

- Development (1,940)

- Appointments/People on the Move (1,821)

- Smart Strategies (1,275)

- Finance (1,265)

hotelonlinenewsInstagram post 17870090452391124Instagram post 17976176743256949Instagram post 17993811919233333Follow on Instagram

Tags

hotel historynobody asked mestanley turkelthe palace hotelthe palace hotel san francisco

RELATED NEWS:

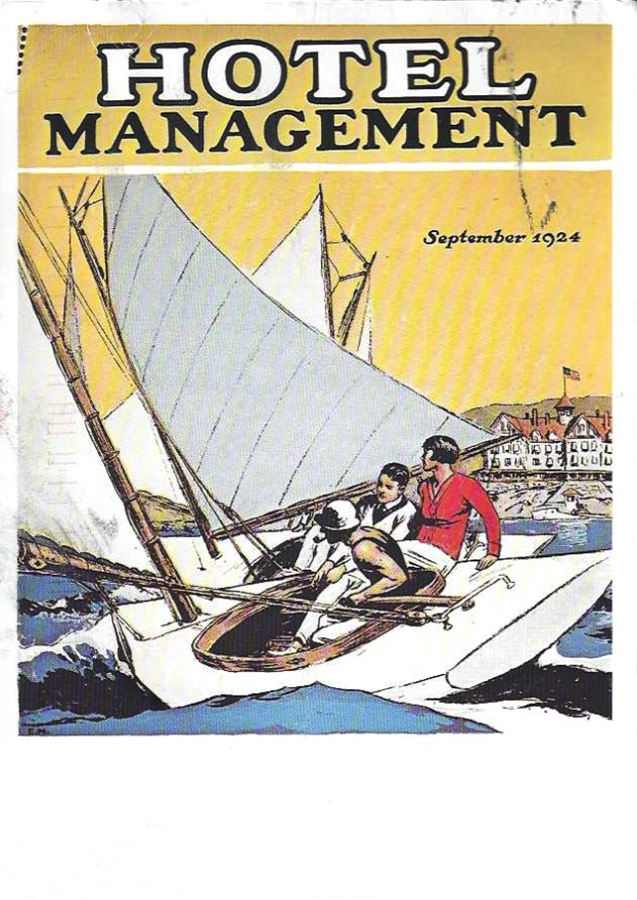

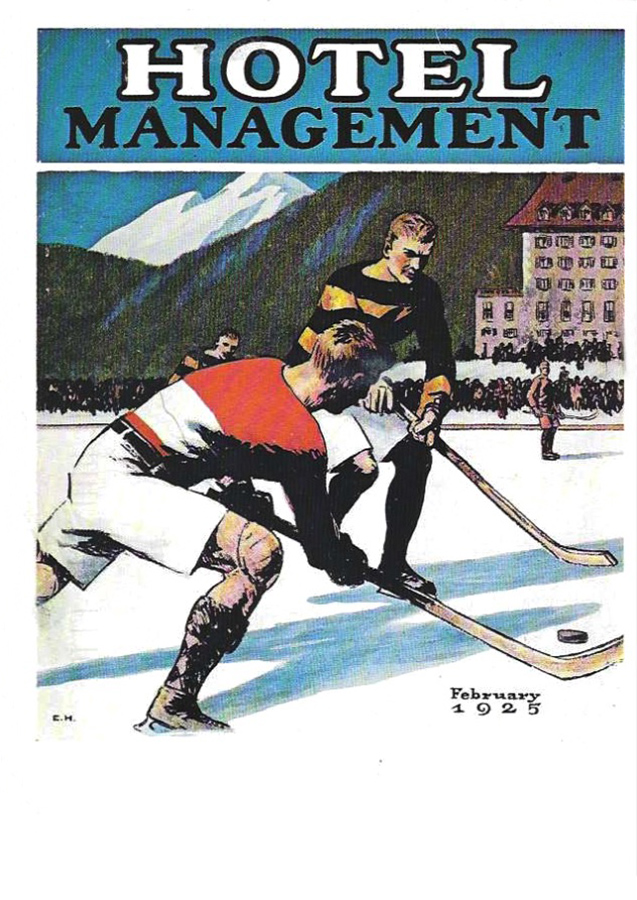

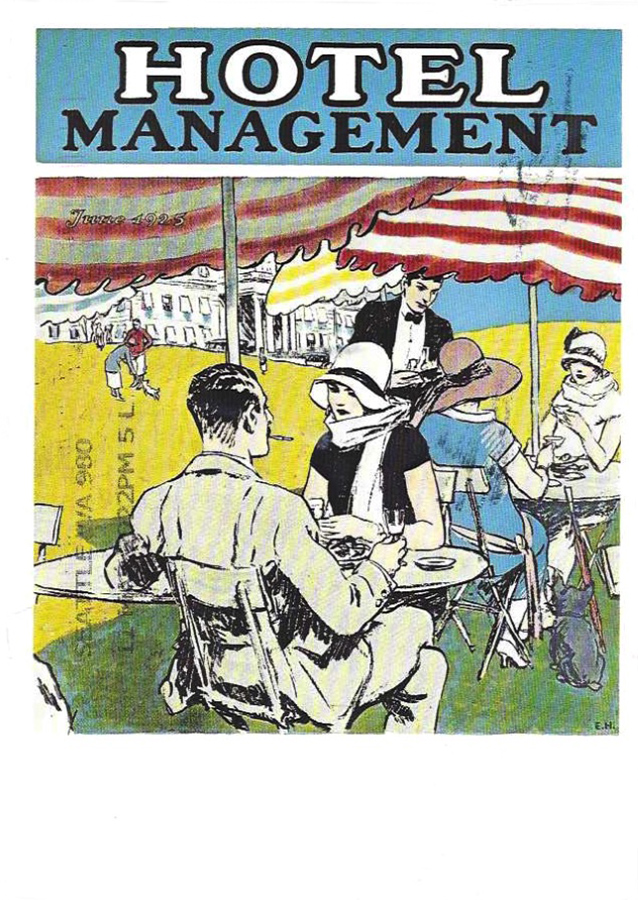

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 267: Hotel History: Famous Artist Edward Hopper and His Hotel Management PaintingsNobody Asked Me, But… No. 265: Hotel History: Asian American Hotel Owners AssociationNobody Asked Me, But… No. 264: Hotel History: Palmer House (1871), Chicago, IllinoisNobody Asked Me, But… No. 263: Hotel History: Frederick Law OlmstedNobody Asked Me, But… No. 262: Hotel History: Tampa Bay HotelNobody Asked Me, But… No. 261: Hotel History: The Homestead, Hot Springs, VirginiaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 260: Hotel History: Terminal City, The Roosevelt Hotel and The Postum Building, New YorkNobody Asked Me, But… No. 259: Hotel History: The Greenbrier, White Sulphur Springs, West VirginiaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 258: Hotel History: The Willard Hotel, Washington, D.C.Nobody Asked Me, But…. No. 257: Hotel History: El Tovar & Hopi Gift ShopNobody Asked Me, But… No. 256: Hotel History: Severin Hotel Indianapolis, IndianaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 255: Hotel History: Shelton Hotel, New YorkNobody Asked Me, But… No. 254: Hotel History: St. Regis HotelNobody Asked Me, But… No. 253; Hotel History: Hotel PennsylvaniaNobody Asked Me, But… No. 252: Hotel History: Libby’s Hotel and BathsNobody Asked Me, But… No. 251: Wish You Were Here: A Tour of America’s Great Hotels During the Golden Age of the Picture Post CardNobody Asked Me, But… No. 250: Hotel History: Mohonk Mountain House, New Paltz, New YorkNobody Asked Me, But… No. 249: Hotel History: Ocean House at Watch HillNobody Asked Me, But… No. 248: Hotel Theresa, New York, N.Y. (1913)Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 247: Hotel History: Driskill Hotel, Austin, Texas