Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 205: Hotel History: Frederick Henry Harvey

November 27, 2018 1:30pm

by Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Hotel History: Frederick Henry Harvey (1835-1901)

Just one hundred years ago, two architectural jewels opened at the Grand Canyon. They are the 95-room El Tovar Hotel and the Hopi House Indian Arts Building. Both reflect the foresight and entrepreneurship of Fred Harvey, an immigrant from England, whose business ventures eventually included restaurants, hotels, newsstands and dining cars on the route of the Sante Fe Railroad. The partnership with the Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe introduced many new tourists to the American Southwest by making rail travel comfortable and adventurous. Employing many Native-American artists, the Fred Harvey Company also collected indigenous examples of basketry, beadwork, Kachina dolls, pottery and textiles.

Fred Harvey arrived in the United States in 1850 at 15 years of age. His first job was a “pot walloper”, a dishwasher in New York City at the Smith and McNeill Café. Harvey made a career change and worked for railroads with travel opportunities for twenty years all over the United States. He learned first-hand what travelers in the West had to endure: uneatable dry biscuits, greasy ham and weak coffee. He even traveled on the Hannibel & St. Joseph known as the “Horrible & Slow Jolting”. After rejection by the Burlington Railroad, Harvey struck a deal with Charles Morse, president of the Santa Fe Railway. With only a handshake to seal their agreement, the two companies began a long and fruitful partnership.

The railroad travelers of that era moved through Chicago on a slow journey westward on hard board seats in overcrowded crude coaches. At a time when most railroad food was poor and even inedible, Fred Harvey provided appetizing and affordable meals in comfortable dining quarters. He opened his first railroad restaurant in Topeka, Kansas in 1876 where good food, spotless dining rooms, and courteous service brought booming business.

The Santa Fe Railway provided the buildings for the Harvey restaurants where the passenger trains would stop twice daily for meals. The railroad carried all the produce and supplies needed by the Harvey restaurants including transporting the dirty laundry. Fred Harvey hired, trained and supervised all personnel and provided for food and service. Harvey’s policy was “maintenance of standards, regardless of cost.” He believed that profits would grow if the food and service were excellent. “Meals by Fred Harvey” became the slogan of the Sante Fe Railway. To maintain this excellence, he hired and trained girls of the finest character as waitresses, the famous “Harvey Girls”.

Harvey placed ads in Eastern and Midwestern newspapers that read: “Wanted, young women of good character, attractive and intelligent, 18 to 30 years of age as waitresses in Harvey Eating Houses in the West. Good wages with room and meals furnished.” Harvey Girls were trained to high standards of prompt and courteous service. They were the key to serving hundreds of passengers in about 20 minutes…the average length of time a train would need for servicing. Only white women were hired as Harvey Girls with no black women and only a few Hispanic and Indian women who ever served as waitresses. White European immigrant women were apparently acceptable. Minority workers, male and female, worked in the Harvey kitchens and hotels where they served as maids, dishwashers and pantry girls. Harvey had no shortage of applicants. It is estimated that a hundred thousand women applied from 1883 until the 1960s.

Harvey Girls all wore the same uniform, outfits befitting a nun: a long-sleeved black dress with a stiff “Elsie” collar, black shoes, black stockings and hairnets. The company furnished a full white wrap-around apron so stiffly starched that it had to be pinned to a corset. Harvey Girls wore no jewelry, no makeup and chewed no gum. They lived in dormitories where they were closely supervised by their manager (or manager’s wife), and curfews were strictly enforced in the early years. They were looked after as carefully as boarding school students in female seminaries in the East. They worked very hard and their eight-hour-a-day shifts were often split to conform to train schedules. They were told what to wear, where to live, whom to date and what time to go to bed. When the Harvey Girls were recruited in the early years, they agreed not to marry for at least a year.

Will Rogers wrote about the Harvey Girls:

“In the early days, the traveler fed on the buffalo. For doing so, the buffalo got his picture on the nickel. Well, Fred Harvey should have his picture on one side of the dime and one of his waitresses with her arms full of delicious ham and eggs on the other side, ‘cause they have kept the West supplied with food and wives.”

One of the reasons for the Harvey Houses’ success was their ability to serve fresh, high quality meat, seafood, and produce at remote locations across the Southwest. Trains would deliver beef from Kansas City, seafood and produce from southern California year-round.

Harvey House workers were able to handle large numbers of passengers in a short amount of time because the conductors on the train would get menu selections from the passengers and that information would be teletyped ahead to the Harvey House cooks. When the train pulled into the station and the passengers began to get off the train, a white-coated Harvey House staffer would hit a brass gong which stood outside the entrance to the restaurant. This let passengers known instantly where to come, and the Harvey Girls were ready to serve them.

Harvey operations at Union Stations in Cleveland, Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago and Los Angeles included newsstands, gift shops featuring Indian jewelry and weavings, barber shops, liquor stores, private dining rooms, restaurants, coffee shops, cafeteria, haberdashery, candy and fruit stands, miniature department store, cocktail lounges and soda fountains. Harvey was among the first to market its own name–brand “designer” goods: Fred Harvey hats, shirts, shaving cream, candy, playing cards, even Harvey Special Blend whiskey. Except for the prohibition years, Harvey sold exclusively a Scotch distilled by Ainslie & Heilbron in Glasgow. As a forerunner to Starbucks, Harvey packaged its own select coffee for public sale in 1948. The blend was already famous among Sante Fe travelers and Harvey sold 7,000 pounds in the first two weeks. The press dubbed him “Civilizer of the West” and one article from the 1880s said “he made the desert blossom with beefsteak and pretty girls.”

The Harvey company built luxurious resort hotels within sightseeing distance of major western attractions in national parks like the Grand Canyon and the Petrified Forest.

In 1870, Harvey built the Clifton Hotel in Florence, Kansas which resembled a fine English home with fountains and candelabra in the surrounding garden and luxurious guest accommodations inside including an elegant dining room. At the turn of the century, another Harvey House of equal beauty was the Bisonte Hotel in Hutchinson, Kansas followed by the Sequoyah in Syracuse and El Vaquero in Dodge City, all built in Spanish Mission style.

The chaotic Kansas frontier included a transient population of cowboys and herd bosses, cattle-selling Texans, prostitutes and saloon-buffs. Harvey built the Arcade Hotel in “bloody Newton, the wickedest town in the West”, after the cattle industry moved to Dodge City. Later, Harvey moved his district headquarters to Newton from Kansas City including construction of a major dairy, an ice plant, meat locker-rooms, a creamery, a poultry feeding station and produce plant, a carbonating plant for bottling soda pop and a modern steam laundry.

As the Santa Fe Railway moved across Kansas to Colorado and to New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas, Harvey hotels opened every hundred miles or so. New Mexico was the home of sixteen, five of which were among the most beautiful in the system: the Montezuma and Castaneda in Las Vegas (NM), La Fonda in Sante Fe, the Alvarado in Albuquerque, El Navajo in Gallup and El Ortiz in Lamy.

Each of these hotels was unique but perhaps none more so than the long-forgotten Montezuma Hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico. An enormous castle-like structure, built adjacent to hot mineral springs, it was the largest wood frame building in the country with 270 rooms and an eight-story tower. Its connected spa-bathhouses served five hundred people a day and competed with the finest health resorts in the United States and Europe. After it burned to the ground in 1884, Harvey and the Santa Fe immediately rebuilt the million dollar hotel. This second structure also suffered a serious fire and was again replaced in 1899. After Harvey’s El Tovar Hotel opened in 1905 at the Grand Canyon, the Montezuma closed.

From 1901 through 1935, the Harvey Company and the Sante Fe built twenty three hotels of which only the following are still in operation: El Tovar and the Bright Angel Lodge in the Grand Canyon, Arizona and La Fonda in Sante Fe, New Mexico.

This article is excerpted from my book: “Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry” AuthorHouse 2009

Please Take Note

My newest book has been published by AuthorHouse: “Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher.”

My Other Published Hotel Books

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

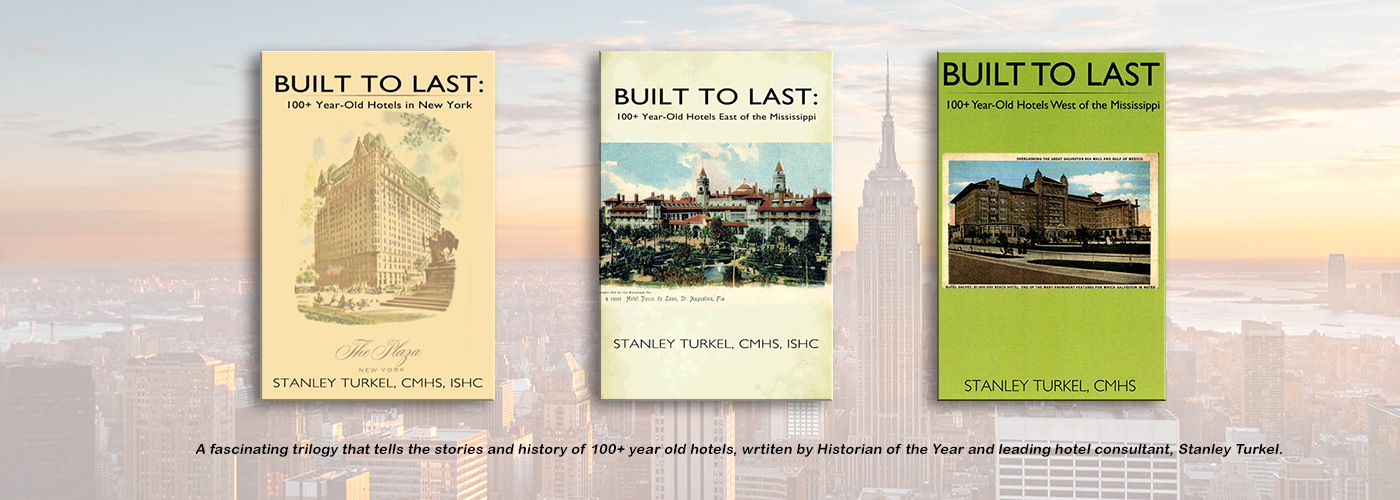

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

All of these books can also be ordered from AuthorHouse by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com and clicking on the book’s title.

If You Need an Expert Witness:

For the past twenty-six years, I have served as an expert witness in more than 40 hotel-related cases. My extensive hotel operating experience is beneficial in cases involving:

- slip and fall accidents

- wrongful deaths

- fire and carbon monoxide injuries

- hotel security issues

- dram shop requirements

- hurricane damage and/or business interruption cases

Feel free to call me at no charge on 917-628-8549 to discuss any hotel-related expert witness assignment.

About Stanley Turkel

Stanley Turkel was designated as the 2014 and the 2015 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of hotel history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion and a greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Turkel is a well-known consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases, provides asset management and hotel franchising consultation. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

Contact: Stanley Turkel

stanturkel@aol.com / 917-628-8549

Related News

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 203: Hotel History: The Skirvin Hotel, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (225 Rooms)

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 202: Hotel History: Mayflower Hotel, Washington, D.C.

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 201: Hotel History: Architect Morris Lapidus

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 200: Hotel History: Cesar Ritz and Auguste Escoffier

Nobody Asked Me, But…No. 197: Hotel History: Ralph Hitz (1891-1940)

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 195: Hotel History: The Elephantine Colossus Hotel

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 194: Hotel History: John McEntee Bowman (1875-1931)